Working at ABB’s research, development and commercialization of Intelligent Shipping Program, Kalevi Tervo, Corporate Executive Engineer and Global Program Manager at ABB’s Marine & Ports division has been part of the team bringing solutions to market that use predictive algorithms to improve safety, efficiency and automation in ship maneuvering, navigation, energy systems and operations.

Tervo has worked extensively on developing autonomous ship control technology, including electronic lookout and autonomous collision avoidance. “While real life efforts have proven the capabilities of navigational automation at sea, for instance during the autonomous tug project in Singapore [1], the more we work with the topic, the clearer it becomes that humans and automation are fundamentally different. So different, that the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) regulations’ demand for automation systems to deliver ‘equivalent or better’ performance than humans loses its meaning –at least on a function level,” he says.

Seeing the need for more research from the industry perspective, Tervo initiated and took the role as Chairman of the Steering Committee for the Enablers and Concepts for Automated Maritime Solutions (ECAMARIS) project, led by VTT Technical Research Centre [2]. The collaboration between ABB and Aalto University in ECAMARIS-project also deepened the understanding of what shipping does and does not need from automation.

“While autonomous systems may seem easy to comprehend, the rapid advances in the introduction of automated functionality alongside human crew mean that the relationship between humans and technology is increasingly complex and fast-evolving,” Tervo says.

Completed last year, ECAMARIS focused on autonomous technology as a source of added value in maritime operations, based on potential for the relocation of the ship bridge, a conditionally and periodically less-manned bridge, and a conditionally and periodically unmanned bridge. The study’s objective was to consider the resulting potential for increasing cargo capacity, reducing costs and emissions per unit carried, lowering navigational accident risks and reducing crew numbers.

The most profound gain from the three-year study was a better understanding of human-automation teaming, and how it is key to optimizing vessel performance.

Human-automation teaming

Douglas Owen, a Human Factors Consultant at Risk Pilot AB, and a Doctoral Student at Aalto University in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship Technology and System Resilience believes the ECAMARIS project made progress towards understanding the sophisticated relationship between technology and humans working at sea.

“A lot of the discussion on autonomous ships over the last 10 years has been informed more by science fiction than reality,” says Owen. “ECAMARIS reconfirmed our understanding that whenever we introduce technology to a ship system, it fundamentally changes the ship and the way people work on it.”

Improving safety and efficiency – those must be the drivers for more maritime automation; otherwise, why are you bringing it to the table?

Meriam Chaal, a former seafarer and a researcher in maritime safety engineering focusing on defining the safety requirements and verification procedures for autonomous ship systems. She works as postdoctoral researcher at Aalto University and believes that the work done in ECAMARIS advanced our understanding of how future maritime automation and human roles together impact the safety levels.

“Improving safety and efficiency – those must be the drivers for more maritime automation; otherwise, why are you bringing it to the table? Because we must acknowledge that a collaboration between humans and technology can result in worse as well as better safety,”, she points out. “ECAMARIS was an opportunity to start building the knowledge needed to assess such systems and to explore which safety methods are adequate.”

Kalevi Tervo, Corporate Executive Engineer and Global Program Manager at ABB’s Marine & Ports division

Douglas Owen, Human Factors Consultant at Risk Pilot AB, and Doctoral Student at Aalto University in Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship Technology and System Resilience

Meriam Chaal, Postdoctoral researcher at Aalto University

Overlooking the importance of human-automation teaming and ignoring the fact that introducing automation always changes the entire system, including user roles, has led to many disastrous examples where the implementation of automated systems has failed. Military ‘friendly fire’ incidents due to over-reliance on automation and naval accidents where confusion from automated steering systems has led to incorrect determination that the system malfunctioned are but two examples, says Owen. Multiple recent accidents were attributable to the crew’s misunderstanding of the ship’s augmented automation systems – highlighting the importance of human-centered design, adds Chaal.

“Our goal is to add value and – when we introduce automation for a specific purpose, we also need to make sure we are not degrading some other function where humans and automation work together,” Chaal points out. “We want the new functionality to benefit performance in all respects.”

Real-world relationships

It was quickly apparent that seafarer interviews would be critical to ensure ECAMARIS became a substantive contribution to autonomous ship technology, says Chaal. “Understanding who did what, how tasks were split, and how crew interacted with each other as well as with technology were essential to establishing whether our concept of the digital crew member matched reality.”

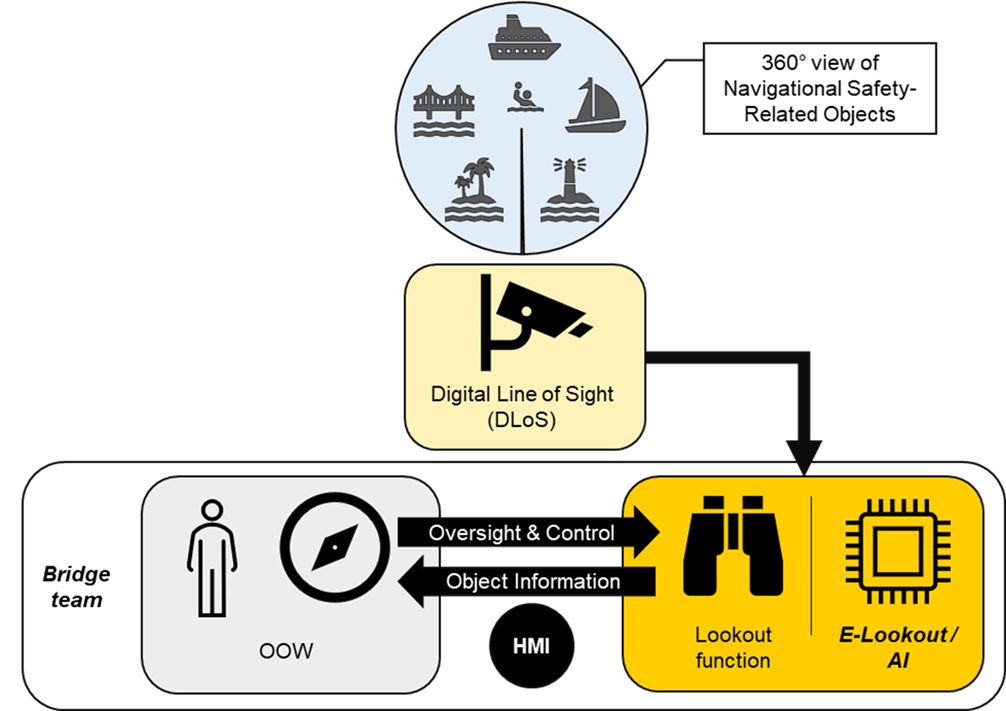

With the interviews, what began as a simple concept of the digital crew member soon needed iterations to add functions such as feedback on system health, awareness of the operational envelope, and alert when nearing its limits, all communicated to the Officer of the Watch (OOW).

Automated systems always work within their operational envelope, while people don’t necessarily, or at least their operational envelope is harder to define.

In some ways, the interviews confirmed what seafarers will already know: effective operations rely on teamwork as well as technology. However, as Tervo observes, by focusing on specific roles, the testimony teased out how seafarers at the sharp end experience the impact of automation.

“When we automate part of the work that was previously done by a human, in one sense we create a ‘digital crew member’ to work relentlessly alongside the humans on board,” he says. “But automated systems always work within their operational envelope, while people don’t necessarily, or at least their operational envelope is harder to define.”

People also perform undocumented tasks, use initiative and take responsibility when they need to.

For instance, an electronic lookout could provide an instantaneous response and pinpoint accuracy, but it doesn't have expectations, memory or decision-making capacity beyond what is programmed into it, at least not in the way a human does.

“There is more to the role of the human lookout than simply relaying information to the OOW in an orderly fashion with the best possible accuracy,” says Tervo. “It’s also more than a bi-directional exchange of information. People also perform undocumented tasks, use initiative and take responsibility when they need to.”

Furthermore, while humans use formal procedures and hazard checklists to counter risk, they also look beyond the bullet points. A human being may also decide that additional information is relevant that needs passing on. At the same time, interaction with a digital crew member alone on a specific function could change the role – of the OOW, says Tervo.

“A human bridge team will have a common understanding of what the ship is going to do – the passage plan, the navigational hazards, the weather forecast and the traffic ahead,” comments Owen. “But circumstances change and challenges arise that take the attention of the OOW, at which point the human lookout might step in to compensate to maintain safety margin. A digital crew member of that caliber would need to be very sophisticated indeed.”

Instead, the ‘operational envelope’ filled by the electronic lookout will be of most use when little is changing – for example during good weather on open seas. For human crew, fatigue and/or boredom can result in mistakes or oversights during these long hours of inactivity.

This is the “automation sweet spot”, says Tervo, when the capabilities of the electronic lookout, the operational safety imperative and opportunities for crew rest coincide. In such circumstances, the bridge could be unattended on a conditional basis.

Even though Tervo cites ECAMARIS as leaving matters “a little open” on conditionality, he, Owen, and Chaal all stress that the research project moved understanding forward sufficiently to recalibrate what shipping should expect from the digital crew member.

Augmentation, not replacement

“One of the problems with the public discourse on autonomous ships has been its focus on replacing crew, whereas the more powerful story is how we augment the crew we already have,” says Owen.

We should see augmentation in the context of the earlier stated aim: improving safety and efficiency. That calls for a systems approach, where technology enhances human capability to achieve better performance together as one system. With today’s available technology, this is possible by carefully defining the operational envelope, ensuring the system delivers its best within clear limits.

“In general, the earlier industry focus on developing autonomous ship technology as fast as possible may have given insufficient attention to the best use cases,” says Tervo.

We are designing automated systems based on about 70 years of field knowledge of the limits of human capabilities and performance.

“Yes, we can automate functionality, but humans and software are not interchangeable: they are good at different things. Autonomous ship technology needs to optimize the contribution both have to offer. Even taking account of advance of AI, our focus is on augmenting rather than replacing the human when we talk about developing the digital crew member.”

“It’s also important to consider that the autonomous ship is developing against the backdrop of a wider discussion which is also maturing,” Owen observes. “We are designing automated systems based on about 70 years of field knowledge of the limits of human capabilities and performance. On the human factor, the focus needs to be on solutions based on Concept of Operations (CONOPS) that defines a realistic role of both human and digital crew members that they can both reliably perform.”

“ECAMARIS has proved very valuable for its scientific approach and challenge to first assumptions on the human-automation interaction,” says Tervo. “This is the best starting point to establish what we want from the system, and a better basis for the CONOPS that drive the most useful functionality – and solutions that are more easily certified.”

“Applied in the correct way, the digital crew member works together with the human crew as a team to improve safety and efficiency, while also enhancing crew working conditions and alertness to deliver additional vessel safety gains.”

“It’s really encouraging that ABB, as an industry leader, is so focused on developments in human-automation teaming, this holds the key to optimizing safety, efficiency and cost management in the real world,” says Owen. “ABB’s take is also increasingly echoed in the CONOPS approach that has been working its way into the verification and validation guidance we see from maritime classification societies.”

References:

[2] https://cris.vtt.fi/en/projects/enablers-and-concepts-for-automated-maritime-solutions